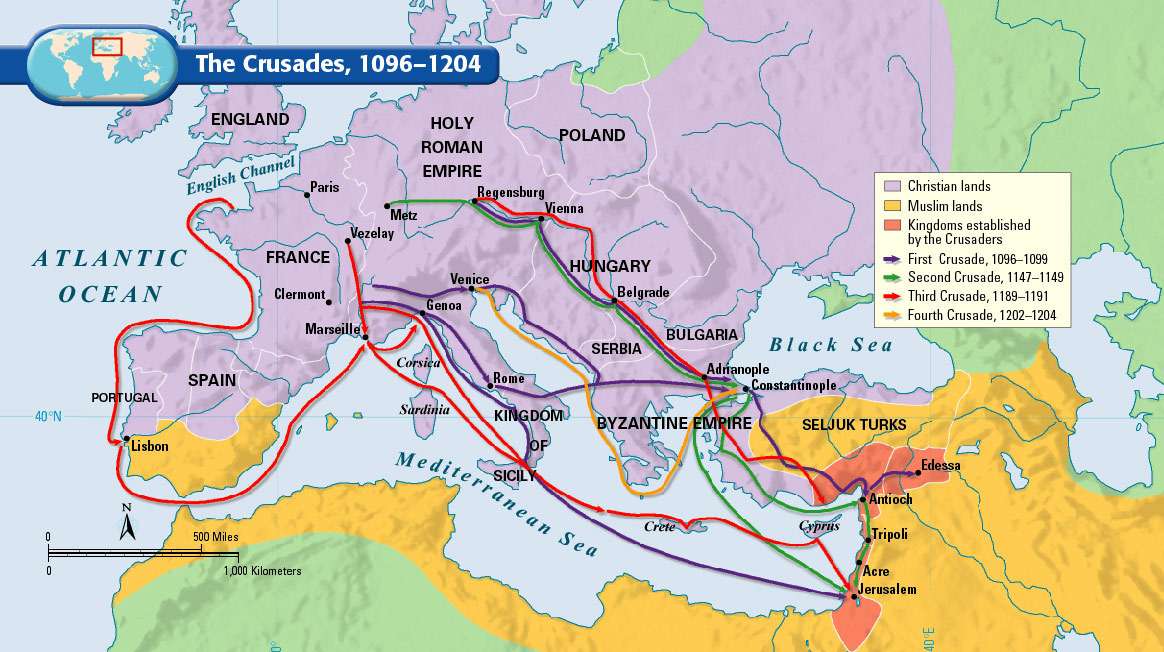

Map of The Crusades, 1096-1204

The Crusades were a series of religious wars sanctioned by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The most commonly known are the campaigns in the Eastern Mediterranean aimed at recovering the Holy Land from Islamic rule but the term Crusades is also applied to other church-sanctioned campaigns. These were fought for a variety of reasons including suppressing paganism and heresy, the resolution of conflict among rival Roman Catholic groups, or for political and territorial advantage. At the time of the early Crusades the word did not exist, only becoming the leading descriptive term around 1760.

In 1095 Pope Urban II called for the First Crusade in a sermon at the Council of Clermont. He encouraged military support for the Byzantine Empire and its Emperor, Alexios I, who needed reinforcements for his conflict with westward migrating Turks colonising Anatolia. One of Urban’s aims was to guarantee pilgrims access to the Eastern Mediterranean holy sites that were under Muslim control but scholars disagree as to whether this was the primary motive for Urban or those who heeded his call. Urban’s strategy may have been to unite the Eastern and Western branches of Christendom, which had been divided since the East–West Schism of 1054 and to establish himself as head of the unified Church. The initial success of the Crusade established the first four Crusader states in the Eastern Mediterranean: the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the County of Tripoli. The enthusiastic response to Urban’s preaching from all classes in Western Europe established a precedent for other Crusades. Volunteers became Crusaders by taking a public vow and receiving plenary indulgences from the Church. Some were hoping for a mass ascension into heaven at Jerusalem or God’s forgiveness for all their sins. Others participated to satisfy feudal obligations, obtain glory and honour or to seek economic and political gain.

The two-century attempt to recover the Holy Land ended in failure. Following the First Crusade there were six major Crusades and numerous less significant ones. After the last Catholic outposts fell in 1291 there were no more Crusades but the gains were longer lasting in Northern and Western Europe. The Wendish Crusade and those of the Archbishop of Bremen brought all the North-East Baltic and the tribes of Mecklenburg and Lusatia under Catholic control in the late 12th-century. In the early 13th century the Teutonic Order created a Crusader state in Prussia and the French monarchy used the Albigensian Crusade to extend the kingdom to the Mediterranean Sea. The rise of the Ottoman Empire in the late 14th-century prompted a Catholic response which led to further defeats at Nicopolis in 1396 and Varna in 1444. Catholic Europe was in chaos and the final pivot of Christian–Islamic relations was marked by two seismic events: the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 and a final conclusive victory for the Spanish over the Moors with the conquest of Granada in 1492. The idea of Crusading continued, not least in the form of the Knights Hospitaller, until the end of the 18th-century but the focus of Western European interest moved to the New World.

Modern historians hold widely varying opinions of the Crusaders. To some, their conduct was incongruous with the stated aims and implied moral authority of the papacy, as evidenced by the fact that on occasion the Pope excommunicated Crusaders. Crusaders often pillaged as they travelled, and their leaders generally retained control of captured territory instead of returning it to the Byzantines. During the People’s Crusade, thousands of Jews were murdered in what is now called the Rhineland massacres. Constantinople was sacked during the Fourth Crusade. But the Crusades had a profound impact on Western civilisation: they reopened the Mediterranean to commerce and travel (enabling Genoa and Venice to flourish); they consolidated the collective identity of the Latin Church under papal leadership; and they constituted a wellspring for accounts of heroism, chivalry, and piety that galvanised medieval romance, philosophy, and literature. The Crusades also reinforced the connection between Western Christendom, feudalism, and militarism.

Beginning in the 7th century, Muslim rulers began expanding their territories into Christian Roman/Byzantine lands, conquering Egypt and the Levant, and gradually taking over all of North Africa, much of Southwest Asia, and most of the Iberian Peninsula. The Eastern Romans, or Byzantines, partially recovered lost territory on numerous occasions but over time gradually lost all but Anatolia and parts of Thrace and the Balkans. In the West, the Roman Catholic kingdoms of northern Iberia launched a series of campaigns known as the Reconquista to reconquer the peninsula from the Arabized Berbers known as Moors (who called it al-Andalus). The conquered Iberian principalities are not customarily called Crusader states, except for the Kingdom of Valencia, despite fitting the general criteria

Professor Barber indicates that, in the Crusader State of the Kingdom of Jerusalem the Holy Sepulchre was added to in the 7th century and rebuilt in 1022, “after a previous collapse”. “In 691-2 Caliph Abd al Malik had built a great dome over the rock here, a place sacred to all three great religions”

In 1071, the Byzantine army was defeated by the Muslim Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert, resulting in the loss of most of Asia Minor. The situation represented a serious existential threat for the Eastern Orthodox Byzantine Empire. The Emperor sent a plea to the Pope in Rome to send military aid with the goal of restoring the formerly Christian territories to Christian rule. The result was a series of western European military campaigns into the eastern Mediterranean, known as the Crusades. Unfortunately for the Byzantines, the crusaders had no allegiance to the Byzantine Emperor and so established their own states in the conquered regions, including the heart of the Byzantine Empire itself.

The Crusader states, also known as Outremer, were a number of mostly 12th- and 13th-century feudal states created by Western European crusaders in Asia Minor, Greece and the Holy Land, and during the Northern Crusades in the eastern Baltic area. The name also refers to other territorial gains (often small and short-lived) made by medieval Christendom against Muslim and pagan adversaries. The Crusader States in the Levant were the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli and the County of Edessa

The first four Crusader states were created in the Levant immediately after the First Crusade:

The first Crusader state, the County of Edessa, was founded in 1098 and lasted until 1150.

The Principality of Antioch, founded in 1098, lasted until 1268.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem, founded in 1099, lasted until 1291, when the city of Acre fell. There were also many vassals of the

Kingdom of Jerusalem, the four major lordships (seigneuries) being:

The Principality of Galilee

The County of Jaffa and Ascalon

The Lordship of Oultrejordain

The Lordship of Sidon

The County of Tripoli, founded in 1104, with Tripoli itself conquered in 1109, lasted until 1289.

The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia had its origins before the Crusades, but was granted the status of a kingdom by Pope Innocent III, and later became fully westernized by the (French) Lusignan dynasty.

During the Third Crusade, the Crusaders founded the Kingdom of Cyprus. Richard I of England conquered Cyprus on his way to Holy Land. He subsequently sold the island to the Knights Templar who were unable to maintain their hold because of a lack of resources and a rapacious attitude towards the local population which led to a series of popular uprisings. The Templars promptly returned the island to Richard who resold it to the displaced King of Jerusalem Guy of Lusignan in 1192. Guy went on to found a dynasty that lasted until 1489, when the widow of James II The Bastard, Queen Catherine Cornaro, a native of Venice, abdicated her throne in favour of the Republic of Venice, which annexed the island. For much of its history under the Lusignan Kings, Cyprus was a prosperous Medieval Kingdom, a commercial and trading hub of Western Christendom in the Middle East. The Kingdom’s decline began when it became embroiled in the dispute between the Italian Merchant Republics of Genoa and Venice. Indeed, the Kingdom’s decline can be traced to a disastrous war with Genoa in 1373–74 which ended with the Genoese occupying the principal port City of Famagusta. Eventually with the help of Venice, the Kingdom recovered Famagusta but by then it was too late and in any event, the Venetians had their own designs on the island. Venetian rule over Cyprus lasted for just over 80 years until 1571, when the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Selim II Sarkhosh invaded and captured the entire island. The battle for Cyprus between Venice and the Ottoman Empire was immortalized by William Shakespeare in his play Othello, most of which is set in the port city of Famagusta on the eastern shores of the island.

After the Fourth Crusade, the territories of the Byzantine Empire were divided into several states, beginning the so-called “Francocracy” (Greek: Φραγκοκρατία) period:

The Latin Empire in Constantinople (1204–1261)

The Kingdom of Thessalonica (1205–1224)

The Principality of Achaea (1205–1432)

The Lordship of Argos and Nauplia (1212–1388)

The Duchy of Athens (1205–1458)

The Margraviate of Bodonitsa (1204–1414)

The Duchy of Naxos (1207–1579)

The Duchy of Philippopolis (1204–1230)

Collection: european-history - Tags: crusades